Why US Workers Have Lost Leverage

A 1970 contract negotiation between GE and its unionized workforce is unimaginable today.

A strike then slowed production for months at 135 factories around the country. With inflation running at 6 percent annually, the company offered pay raises of 3 percent to 5 percent a year for three years. The union rejected the offer, and a federal mediator was brought in. GE eventually agreed to a minimum 25 percent pay raise over 40 months.

“They said we couldn’t, but we damn sure did it,” one staffer said about his union’s victory.

Former Wall Street Journal editor Rick Wartzman tells this story in his book about the rise and fall of American workers through the labor relations that have played out at corporate stalwarts like GE, General Motors, and Walmart.

Critics use examples like GE to argue that unions had it too good – and they have a point. But that’s old news. What’s relevant today is that the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction, and blue-collar and middle-class Americans seem barely able to keep their heads above water even in a long-running economic boom.

Critics use examples like GE to argue that unions had it too good – and they have a point. But that’s old news. What’s relevant today is that the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction, and blue-collar and middle-class Americans seem barely able to keep their heads above water even in a long-running economic boom.

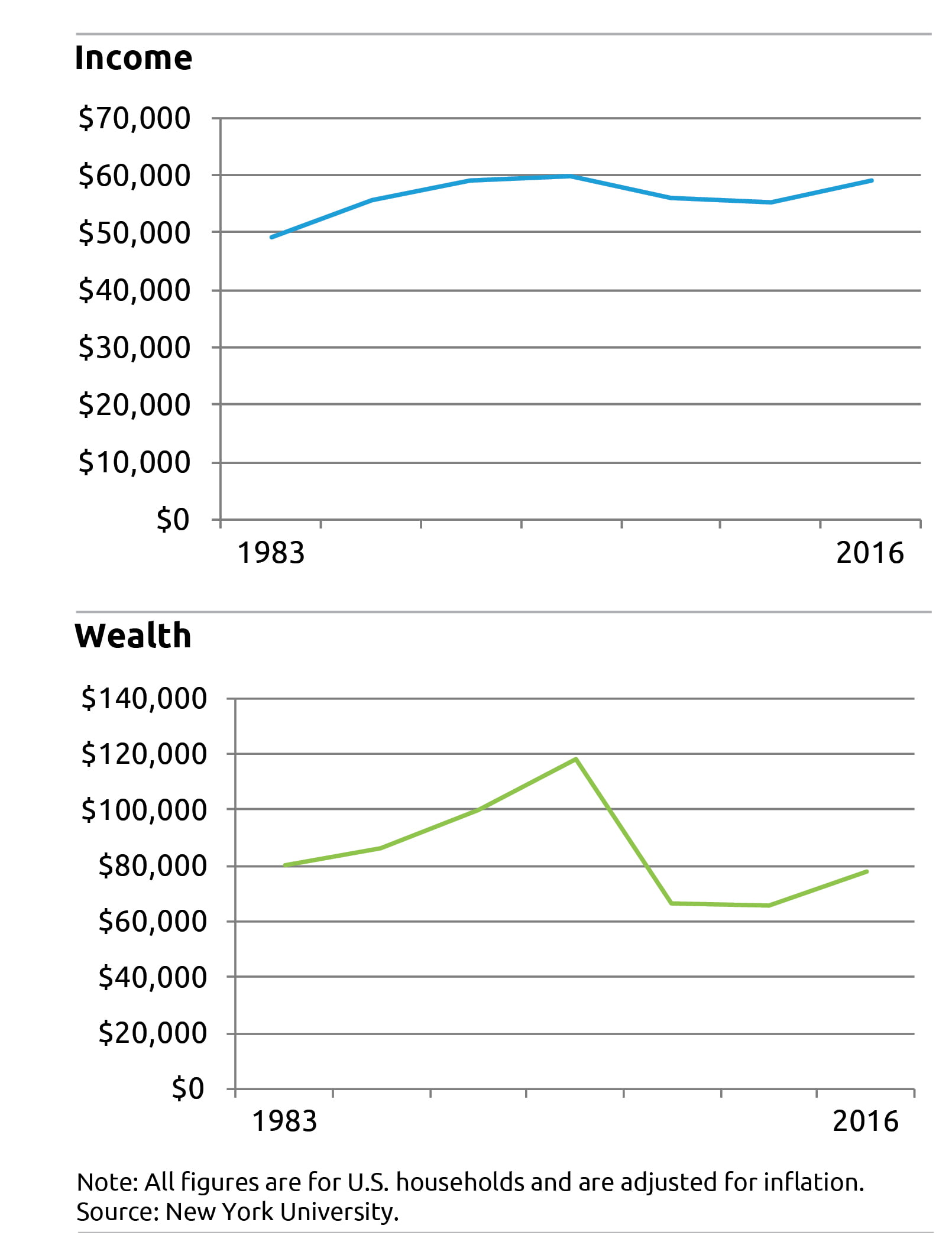

New York University economist Edward Wolff in a January report estimated that workers lost much ground in the 2008 recession and never recovered. The typical family’s net worth, adjusted for inflation, is no higher than it was in 1983 and far below the pre-recession peak. Granted, workers’ wages have gone up recently, though barely faster than inflation, but they had been flat for 15 years. Workers are also funding more of their retirement and health insurance.

Wartzman’s theme in “The End of Loyalty: the Rise and Fall of Good Jobs in America” is that the system no longer works for regular people, because companies have weakened or broken the social contract they once had with their workers.

The loss of employer loyalty is one way to look at the state of labor today. The loss of workers’ leverage against global corporations is another.

The decline of unions to only 6.5 percent of private-sector workers today is an important reason for this loss of leverage, according to a 2017 analysis published by Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Business. The researchers found that wages are lower in the industries that are dominated by a few major players, because workers have less bargaining power against these large employers. But when there is union representation in a concentrated industry, the unions have had more success in protecting wages.

Unions have been undermined by powerful economic forces. Technology has replaced manpower, and globalization has made it possible for companies to move factories to low-wage countries. Of course, these trends have increased workers’ living standards by giving them smart phones and an endless supply of inexpensive consumer goods from China. But the movement of factories overseas has indirectly dealt another major blow to workers: the economy has tilted increasingly toward the service sector in recent decades. Services industries typically don’t have unions and offer lower pay and skimpier benefits, various federal data show, and rank-and-file retail workers often have unreliable or unpredictable work schedules.

When Walmart employees attempted to organize stores and meat-packing plants in the 1990s and early 2000s, Wartzman writes, the nation’s largest employer threatened to close these operations. Meanwhile, full-time workers have shrunk to half of the retailer’s workforce. One recent development returned a bit of leverage to workers: the current tight job market and a very low unemployment rate. In February, Walmart raised its hourly wage across the board from $10 to $11 per hour, putting it in the range of the highest state minimum wages.

Consider another recent trend that has weakened workers: the rise of the gig economy. This labor force of contingent workers – freelancers, temp-agency and seasonal help, and the carpenters and dog walkers finding jobs on TaskRabbit – now make up 15 percent of the U.S. labor force, which is more than double the union rate in the private sector. A federal study found that contingent workers often lack benefits. This isn’t a necessarily a problem for people who get health insurance through a spouse, or for consultants and former executives who can charge a premium for their work.

But most gig workers, by virtue of being lone actors, lack the leverage to negotiate a better deal with an employer. Uber recently angered its Miami drivers, for example, by passing on to them just 1 penny per mile of a 10 percent hike in customer fares.

Stagnant wages are a symptom of “a long power struggle that workers are losing,” said Jared Bernstein, former chief economic adviser to Vice President Joe Biden.

Workers are increasingly on their own, and it’s not going well. It’s an extremely difficult problem to fix.

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us on Twitter @SquaredAwayBC. To stay current on our blog, please join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here.

Comments are closed.

That worked well when the U.S. was the 600-lb gorilla (and consumers had no choice but to pay those increased embedded costs). But starting (about) in the 80s & especially today, we’re in a global competitive environment & that union mentality now will certainly send those jobs offshore (or the consumers will purchase the lower cost foreign products). In unionized jobs not easily offshored, we see that resulting in workers losing their pensions and retiree health benefits, as well as in other areas students racking up $1.5T in debt.

All workers, including gig workers, have the option of using today’s technology to incrementally invest in themselves and in the stock market to grow their own individual wealth and do even better than they would have otherwise.

But, that takes significant discipline and long-term vision.

Brian is right, and I think of the legacy airlines almost all of them declaring bankruptcy and shedding debt and a large percentage of the pensions they were obligated to pay.

I am much more comfortable with my children having a 401(k) whereby they have portable pensions but have to invest wisely.

Anyone know how well the Apple’s–Facebook–Netflix type companies pay? I get the feeling that they do quite well by their employees.

I can’t speak to how Apple, Facebook and Netflix pay their employees, but it’s been reported that Amazon isn’t paying many of their employees very well. If true, that’s interesting and somewhat surprising, given how Jeff Bezos’ wealth has swelled as the company has grown by leaps and bounds over the years.

People don’t get it. GE has to pay people. Now it gets to pay people less. But then GE has to turn around and sell things to people, as do they all. How can they pay people less and still sell people more?

First, more workers per household (women). Then inadequate retirement savings to offset lost future compensation in retirement, which didn’t effect spending then, and will big time starting now. And then a massive increase in personal debt. Followed by a massive increase in government debt to keep the debt-driven consumer economy from collapsing.

People don’t get it. They should. Workers and consumers are not different people. They are the same people at a different time of day. Total debt, and labor’s share of national income, were flat until 1980, then both soared. The U.S. current account — which had been balanced for decades — went deep into the red at the same time. How do you import more than you export? Debt, and inadequate retirement savings.

Read this.

https://larrylittlefield.wordpress.com/2014/03/09/debt-and-inequality-go-together-rising-debt-is-the-cause-of-rising-inequality/

Anyone who has ever run a balance on their credit card has cooperated in their own economic demise. They paid business more than business paid them.

What the Inequality/Debt chart in that article shows is correlation, not causality.

If all there is is a local economy, then that article is correct – if your employees are the same people you’re selling to and you cut their wages, then they can’t buy your product. But, we’re in a global economy – and your workers may not be your consumers – products can be made and sold anywhere across the globe. Where Country A subsidizes its residents’ purchases, its residents can buy more, but that model is unsustainable – as we see going on in Venezuela right now.

The article’s comment about the Gini Coefficient “….for total household income has risen even more, but that is due to an increase in the number of two-income families, and single parent families, divorce, and people simply choosing to live alone. These are social, not economic, issues…..” is misleading. If your two-income household makes six-figures each because you both have degrees in nuclear engineering and my two-income household both flip burgers at fast-food restaurants, both our household incomes will have risen due to two wage earners, but mine will be in debt, yours won’t.

And that’s our problem – inadequate income, inadequate retirement savings, lost future compensation, massive increase in personal debt, are all related to the same root cause – we talk about it all the time:

– it takes income to afford more than the basics, save for retirement, etc.;

– we know which occupations pay good wages;

– we know what skillsets and qualifications provide access to those occupations;

– and we know the “success sequence” of how to get there.

Wages are paid based on the worker’s skillset. Many Americans haven’t kept their skillsets adapted to and up with the changing global market. Times have changed since my father’s days when he worked for a company for 30 years and got a good pension. Today it takes investing in one’s self, working smarter, choosing the right career, making good economic choices, saving for retirement, improving skills, investing in the market, etc.

No one should be striving for just the “minimum.” Otherwise, even the basics will be out of reach – and that’s where the personal debt that you refer to raises its ugly head.

It’s almost always about personal choices. Otherwise, as you point out, government will step in with very expensive safety net programs.

The data shows those now under 40 were more likely to complete high school, more likely to complete college, less likely to become single parents, less likely to commit crimes, less likely to use illegal drugs.

But they are paid less, on average.

https://larrylittlefield.wordpress.com/2014/12/27/falling-wages-its-not-just-the-millennials-and-its-not-just-the-business-cycle/

And please don’t claim that in the 1960s everyone studied STEM while today they are all hippies getting high. Numbers don’t correspond with that assumption.