The Impact of Taxing Health Premiums

Excluding the health insurance premiums paid by employers and employees from workers’ taxable earnings is the federal government’s largest single tax expenditure, amounting to some $250 billion a year in lost revenue.

Eliminating the exclusions – as some in Washington have proposed – would sharply increase how much is taken out of workers’ paychecks for payroll taxes and for income taxes. But any such proposal would also put more money in their pockets when they retire by increasing the earnings base on which their Social Security benefits are calculated.

Urban Institute researchers Karen Smith and Eric Toder recently estimated the policy’s impact on workers’ taxes and benefits and found that it varied widely for different income groups and among people born in five different decades, the 1950s through the 1990s.

Their analysis took into account the myriad idiosyncrasies of the U.S. tax code, including a regressive payroll tax, a progressive income tax, Earned Income Tax Credits paid to the lowest-wage workers, and the cap on payroll taxes for the highest earners. To evaluate the proposals’ impact, the researchers added the premium amounts paid by both the employer and employee to workers’ taxable incomes – just as the deficit reduction proposals would do.

The resulting tax bite would be largest for the middle class. That’s because middle-income workers are more likely to have employer-provided health insurance than lower-income workers, and their insurance premiums are a larger share of their income than they are for higher-income groups. Under the proposal, middle-income workers’ federal income and payroll taxes would rise by an amount equal to 3.5 percent of their lifetime earnings.

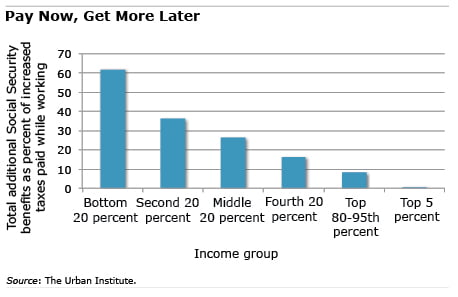

But higher taxes are just one impact of the change. The proposal would also increase Social Security benefits by increasing workers’ total lifetime earnings. One way to evaluate this is to compare workers’ future benefit increases to the additional taxes they would have to pay.

But higher taxes are just one impact of the change. The proposal would also increase Social Security benefits by increasing workers’ total lifetime earnings. One way to evaluate this is to compare workers’ future benefit increases to the additional taxes they would have to pay.

By this measure, the effects are strongly progressive: those at the bottom of the income scale would see much larger increases in their benefits, mirroring Social Security’s progressive benefit formula. The value of the benefit increases shown in the above chart ranged from 62 percent of the additional taxes paid by the lowest-income workers to 26 percent in the middle to less than 1 percent for those in the top 5 percent.

Changing the tax code involves difficult tradeoffs. Under this proposal, workers’ paychecks would shrink, but it would also increase retirement security for those who need it most.

The research reported herein was performed pursuant to a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA or any agency of the federal government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.

Comments are closed.

Today’s system hides the true cost of health care and insurance. Anything to bring transparency is an improvement.

So why can’t costs be offset for middle-income taxpayers with lower tax rates to begin with? Granted, you may need a refundable tax credit to help low-income earners.

By coupling an end to tax breaks with a lower tax rate, you rid the system of distortions and disincentives. Only then can we get to real price discovery on goods and services.

I wonder who is really vested in maintaining entitlements: The intended beneficiaries or the political class presiding over them?

First off, calling the health insurance deduction a “government expenditure” signals a possible attitude that all income belongs to the government and that its the government’s choice to “spend or keep.” It should be clear that income belongs to the individual. It is not an expenditure; it’s a possible source of more tax revenue. Just wanted to be clear on that.

Secondly, I think with the middle class standard of living falling, we would make some people homeless with the increased taxes, all for the “benefit’ that, if they live to 67 (or 68+ I’m thinking this age will move back), they might have a few more bucks.

A family health plan, at $800-1,500/mo, at a 25% tax rate would be $200-375 more out-of-pocket per month under this idea. I’m not sure if any of the authors have 2-3 kids and bills, but losing $2-4k a year would hit a lot of people hard. A fact that I see too often as a financial planner.

I would rather see government take other steps, like shrink, so that either more money could go into Social Security, or at least so we don’t entertain financially devastating proposals like this.

Sorry to be so blunt but that’s how it is out there.

Warmly,

Chris G

Good call, @ChrisG. The idea of taxing health premiums so individuals can further lose economic value by tithing into Social Security and “get more later” is beyond ridiculous.