How Much For the 401(k)? Depends.

How much must 30-somethings save in their 401(k)s to prevent a decline in their living standard after they retire?

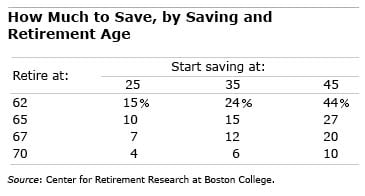

No two people are alike, but the Center for Retirement Research estimates the typical 35 year old who hopes to retire at 65 should sock away 15 percent of his earnings, starting now. Prefer to retire at 62? Hike that to 24 percent. To get the percent deducted from one’s paycheck down into the single digits, young adults should start saving in their mid-20s and think about retiring at 67.

These retirement savings rates are taken from the table below showing the Center’s recent estimates of how much workers of various ages should save to achieve a comfortable retirement; they represent the worker’s contribution plus the employer’s contribution on their worker’s behalf. Expressed as a percent of their earnings, they also vary depending when a worker retires.

To derive these savings rates, the Center’s economists assumed that a retired household with mid-level earnings needs 70 percent of its past earnings. They then subtracted out the household’s anticipated Social Security benefits. The rest has to come from employer retirement savings plans, which determine the percent of pay required to reach the 70 percent “replacement rate.”

To be sure, workers may be able to save less if they have a traditional defined benefit pension or can tap home equity to supplement their retirement income – these were not included in the above calculations. (The calculations are based on a couple of assumptions: that workers’ invested savings earn 4 percent annually, after inflation, and that when they retire, they use their savings to purchase an inflation-indexed annuity.)

Other factors, in addition to age, are implicit in the appropriate savings rate, chief among them the size of a worker’s paycheck. Earnings influence both how much he’ll need to maintain his lifestyle into retirement and how much he’ll get from Social Security.

Workers who earn less will need a larger share of their earnings in retirement. That’s because they often pay lower, or even no, income taxes while they’re employed, so their tax bite does not fall as sharply in retirement as it does for higher earners. The Center estimated replacement rates, based on earnings, using a somewhat different methodology than was used to calculate savings rates.

These replacement rates are 80 percent for low-income workers and 67 percent for high earners.

The good news for low-income workers is that Social Security benefits replace a larger share of their earnings than they do for higher earners.

As the table highlights, savings rates also depend greatly on when workers start saving and when they retire. Early savers make more contributions and earn more on their investments over decades in the labor force. Retire later and a worker benefits from a larger monthly Social Security check, more time to save and invest and from having to fund fewer years in retirement.

The choice here is clear: start early or work longer.

Comments are closed.

It’s interesting that these rates are becoming conventional wisdom at a time when private pensions are a distant memory. Back when the transition was underway, this would have been a rather inconvenient truth.

It is interesting to see how much a relatively slight delay in retirement reduces the required saving. If I am reading the chart correctly, to delay planned retirement from 65 to 70 reduces the required annual saving by 60% or more.

This makes sense. The later retirement means a higher total of retirement saving, because one has saved longer and one has more years of compounding earnings on those savings, a good thing. But the later retirement means fewer remaining years to consume those savings, a bad thing.

If one lowers ones saving rate in reliance on the charts, one is assuming the risk of being unable to remain in the labor force, and thus facing a severe fall in retirement income.

Michael Waggoner, you left out the biggest reason for the required saving rate to drop so drastically with a delayed retirement: the large increase in Social Security payments. Of course, your point about people taking a risk assuming they will be able to remain in the labor force is spot on.

I’m a retired financial advisor and former investment industry executive who finds it ironic that, as in this case, academics use annuitized income streams to model amounts needed to fund retirement. One benefit of course is the predictable cash flows that come from something called “mortality pooling.” With lifetime income annuities we pool our savings with an insurance company, and if you live longer than I do then you in effect get to spend my money. That’s an over-simplification since there’s more than two people in any one annuity product, but you get the idea.

Unfortunately, the majority of today’s financial advisors I’ve spoken with won’t even consider recommending annuitized income products for IRAs or individual client portfolios, usually because they don’t suit their business models (they want to “manage” the money). This means retirees without pensions may often need as much as 35 percent – or even more – in 401(k) savings to achieve the same non-volatile, inflation-adjusted cash flows that a mortality pooling solution can provide. It’s not for everyone (wealthy people are more concerned with inheritances) and there are trade offs and risks with the products that need to be weighed against the features and benefits of more volatile, less predictable solutions.

However, it does seem appropriate that people should, at a bare minimum, be able to at least consider the annuitized income idea when they meet with their trusted advisors to discuss retirement income options. At least for as long as the academics keep using them as examples in their papers!